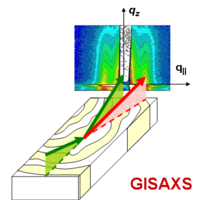

Grazing-incidence small-angle scattering

Okay kiddo, imagine you have a toy car and you want to see what it's made of. You could just look at it, but sometimes you need to use special tools to see things that are too small to see with your eyes.

Scientists have tools to look at really tiny things that are too small to see with their eyes, and one of those tools is called grazing-incidence small-angle scattering (GISAS for short). GISAS helps them look at really tiny, nano-sized things.

Now, imagine that you shine a flashlight on the toy car from straight above, like this: \[ \texttt{Flashlight }\] \[\texttt{Toy car}\] The light hits the car and bounces back up, so you can see the car.

But what if you wanted to look at really small details on the car, like the tiny little bumps or scratches? The flashlight doesn't work well for that – the light just bounces straight back up and you can't see anything tiny.

That's where GISAS comes in. Instead of shining the light straight down, scientists shine the light on the car at a really low angle, like this: \[\texttt{Flashlight}\] \[\texttt{Toy car}\] \

When the light hits the car at this low angle, it bounces off in all sorts of different directions. Some of the light bounces straight back up, but some of it bounces off at different angles.

Scientists can use special detectors to measure all the light that bounces off at different angles. By looking at how much light bounces off at different angles, they can figure out what the little bumps and scratches on the car are made of.

Now, instead of looking at toy cars, scientists use GISAS to study really tiny things like molecules or materials that are too small to see with their eyes. It's like shining a flashlight on the tiny things at a low angle, and measuring how the light bounces off in different directions so they can understand what the tiny things are made of.

Scientists have tools to look at really tiny things that are too small to see with their eyes, and one of those tools is called grazing-incidence small-angle scattering (GISAS for short). GISAS helps them look at really tiny, nano-sized things.

Now, imagine that you shine a flashlight on the toy car from straight above, like this: \[ \texttt{Flashlight }\] \[\texttt{Toy car}\] The light hits the car and bounces back up, so you can see the car.

But what if you wanted to look at really small details on the car, like the tiny little bumps or scratches? The flashlight doesn't work well for that – the light just bounces straight back up and you can't see anything tiny.

That's where GISAS comes in. Instead of shining the light straight down, scientists shine the light on the car at a really low angle, like this: \[\texttt{Flashlight}\] \[\texttt{Toy car}\] \

When the light hits the car at this low angle, it bounces off in all sorts of different directions. Some of the light bounces straight back up, but some of it bounces off at different angles.

Scientists can use special detectors to measure all the light that bounces off at different angles. By looking at how much light bounces off at different angles, they can figure out what the little bumps and scratches on the car are made of.

Now, instead of looking at toy cars, scientists use GISAS to study really tiny things like molecules or materials that are too small to see with their eyes. It's like shining a flashlight on the tiny things at a low angle, and measuring how the light bounces off in different directions so they can understand what the tiny things are made of.